Carnation

Lily Lily Rose

16

x 20 in.

or

Carnation

Lily Lily Rose

31

x 23 in.

Broadway,

The Cotswolds, England |

|

Francis

Davis Millet

Mr.

Sargent at work on Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose

1885-65 |

Photo:

Sargent painting at Broadway

1885-86 |

Studies

|

|

Study of

Polly Barnard for 'Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose'

c. 1885

|

Dorothy Barnard

1885

|

Study

of Barnard Children for Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose (graphite)

1885-86 |

Lily Study for "Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose"

1885-86

|

Japanese Lanterns and Lilies, Study for "Carnation, Lily,

Lily, Rose"

1885-86 |

Back of Child's Head

1885-86

|

Studies for Flowers for "Carnation,

Lily, Lily, Rose"

1880-85

|

Studies for Flowers for "Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose"

1880-85 |

Study of Flowers and Lanterns; verso:

Studies for "Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose;" Comic Heads

1880-85

|

Girl with Lantern

1880-85 |

|

Carnation,

Lily, Lily,

Rose [1]

John

Singer Sargent

-- American painter

1885-1886

Tate

Gallery, London,

England

Oil on canvas

174 x 153.8 cm

(68 1/2

x 60 1/2 in.)

Purchased from

the artist,

1887

Jpg: Tate

Gallery

(Click on image to Step

Closer)

Conceived under the

most unusual

of circumstances, and nurtured in a remarkable setting at Broadway,

this

painting is overwhelmingly held out by the public -- then as well as

today

-- to be the most favored painting of all his work. It is universally

believed

to be one of his masterpieces. Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose, the

title lifted from the light-hearted lyrics of a popular song, is a

triumph

of John's use of light which would never be equaled in quite the same

way.

The

seed of the idea was first planted in the fertile garden of the

Lavington

Rectory in 1884 when Sargent was staying with the Vickers. The white

lilies

in full bloom around the two children in a garden would be the

framework

on which he would mount this most ambitious project. The idea (a purely

fanciful one to be sure) was to capture, not the most perfect sunset,

but

the affect of the most perfect sunset has, in terms of color, shadows

and

light on a scene. But it was more than that. How about the artificial

light

of Chinese lanterns at the precise moment of twilight when lanterns and

sun are at perfect equilibrium! -- Could he paint that magical

transient

moment that lasts no more than

a couple of minutes most -- capture that

most perfect color of mauve when the sun is still flush in the sky and

the lanterns glowing equally? Not create the scene from his mind

or memory of what it would or should look like, but actually capture it

-- could he paint the exquisite beauty between those two

minutes? The

seed of the idea was first planted in the fertile garden of the

Lavington

Rectory in 1884 when Sargent was staying with the Vickers. The white

lilies

in full bloom around the two children in a garden would be the

framework

on which he would mount this most ambitious project. The idea (a purely

fanciful one to be sure) was to capture, not the most perfect sunset,

but

the affect of the most perfect sunset has, in terms of color, shadows

and

light on a scene. But it was more than that. How about the artificial

light

of Chinese lanterns at the precise moment of twilight when lanterns and

sun are at perfect equilibrium! -- Could he paint that magical

transient

moment that lasts no more than

a couple of minutes most -- capture that

most perfect color of mauve when the sun is still flush in the sky and

the lanterns glowing equally? Not create the scene from his mind

or memory of what it would or should look like, but actually capture it

-- could he paint the exquisite beauty between those two

minutes?

Of course not. No

one could paint

in two minutes and even come close to a faithful adaptation no matter

how

prepared he or she was prior. But what if he painted only for those

magical

minutes every day? If he was faithful, if he kept true to the

principles

of Impressionism -- painting only what he saw and not what he thought

he

saw or wanted to see, if he did it every day for two minutes could he

capture

lightning in a bottle so to speak?

It was silly, but

the idea was hatched

in a community of people that weren't constrained by the blinders of

convention.

These were people who could see things that weren't and ask way not?

Sargent

was going to do the impossible and they were all going to help!

He started off by

using Mrs. Millet's

young daughter who was only 5 at the time. They put a wig on her to

lighten

her hair and then propped the poor thing up as if she were

lighting

a Chinese lantern. Everyone in the community took an interest, but the

demands of maintaining an exact pose every day proved to be too much;

so

in her place Mrs. Barnard's two girls stepped in of a more

appropriate

age of seven and eleven.

Edmund

Gosse wrote: "The progress of the picture, when once it began to

advance,

was a matter of excited interest to the whole of our little

artist-coloney.

Everything was used to be placed in readiness, the easel, the canvas,

the

flowers, the demure little girls in their white dresses,before we began

our daily afternoon lawn tennis, in which Sargent took his share. But

at

the exact moment, which of course came a minute or two earlier each

evening,

the game was stopped, and the painter was accompanied to the scene of

his

labors. Instantly, he took up his place at a distance from the canvas,

and at a certain notation of the light ran forward over the lawn with

the

action of a wag-tail, planting at the same time rapid dabs of paint on

the picture, and then retiring again, only with equal suddenness to

repeat

the wag-tail action. All this occupied but two or three minutes, the

light

rapidly declining, and then while he left the young ladies to remove

his

machinery, Sargent would join us again, so long as the twilight

permitted,

in a last turn at lawn tennis"

(Sir Edmund Gosse

letter to Charteris

, P74-75)

"The seasons went

from August till

the beginning of November "Sargent would dress the children in white

sweaters

which came down to their ankles, over which he pulled the dresses that

appeared in the picture. He himself would be muffled up like an Artic

explorer.

At the same time the roses gradually faded and died, and Marshall and

Snelgrive

had to be requisitioned for artificial substitutes, which were fixed to

the withered bushes . . . . In November, 1885, the unfinished

picture

was stored in the Millets' barn. When in 1886 the Barnard children

returned

to Broadway the sittings were resumed.

(Charteris , P75)

For Sargent it

seemed the fun was

in the process. Edwin Howland Blashfield recalled that when he saw the

canvas each morning, the previous evening's work seemed to have been

scraped

off, and that this happened repeatedly at each stage.

(Tate)

"Never for any

picture did he do

so many studies and sketches. He would hang about like a snapshot

photographer

to catch the children in attitudes helpful to his main purpose. 'Stop

as

you are,' he would suddenly cry as the children were at play, "don't

move!

I must make a sketch of you," and there and then he would fly off,

leaving

the children immobile as Lot's wife, to return in a moment

with easel, canvas and

a paint-box.

(Charteris , P74)"

Notes

1) The lyrics in an

earlier version

of Joseph Mazzinghi's song (circa Joseph Mazzinghi's life) has the line

punctuated as "Carnation lily, Lily rose."

I should be the

last to point out

grammatical disparities (and I'm more than a little surprised I caught

it) but reading the title as Mazzinghi might have meant the line to

read,

lets it roll off the tongue more lyrically rather than the plodding --

thump, thump -- as it is now.

It would be

interesting to see how

early in the literature this incorrect form first started. Of course

the

line was meant to be sung and Sargent's intent would have been in the

cadence

of the song itself. I wonder if Sargent's title was always writen this

way?

More

on the song that

inspired

the painting

|

|

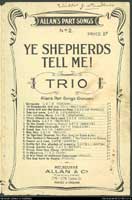

Ye

Shepherds Tell Me

Composed

& arranged for the piano in 3 voices (overlapping lyrics and

harmony)

forte

by

Joseph Mazzinghi (1765-1844)

[first

voice lead]

Ye

Shep-herds tell me, tell me have you seen, have you seen My Flo-ra pass

this way? In shape and feature beau- - -ty's queen. In pastoral,

in pas-to-ral ar-ray

[Chorus]

Shepherds

tell me, tell me have you seen, have you seen My Flo-ra pass this way?

Have you seen, tell me Shepherds have you seen, tell me have you seen

My

Flo-ra pass this way. _____

[second

voice takes lead]

A

wreath a- -round her head, around her head she wore Car-na-

-tion, lil-ly, lil- - -ly, rose; And

in her hand a crook she bore, And sweets . . . her breath

compose.

[Chorus]

Shepherds

tell me, tell me have you seen, have you seen My Flo-ra pass this way?

Have you seen, tell me Shepherds have you seen, tell me have you seen

My

Flo-ra pass this way. _____

The

beau-teous, the beauteous wreath that decks, that decks her head, Forms

her descrip-tion, her de-scription true. Hands lily white, Lips

crim-son

red, and cheeks of ro-sy, ro-sy hue.

See

more about Song

|

Mrs.

Frederick Barnard

1885

(mother

to Barnard children)

|